Brief by Aidan Powers-Riggs, Brian Hart, Matthew P. Funaiole, Scott Thomsett, Simon Zieleniewski, and Tim Rose

Published July 17, 2025

The Issue

Introduction and Key Findings

This brief presents several key findings:

- China’s gallium export controls have incrementally tightened in response to expanding U.S. technology restrictions. Its measures have ratcheted up from licensing requirements and end-user controls to a total export ban targeting the United States.

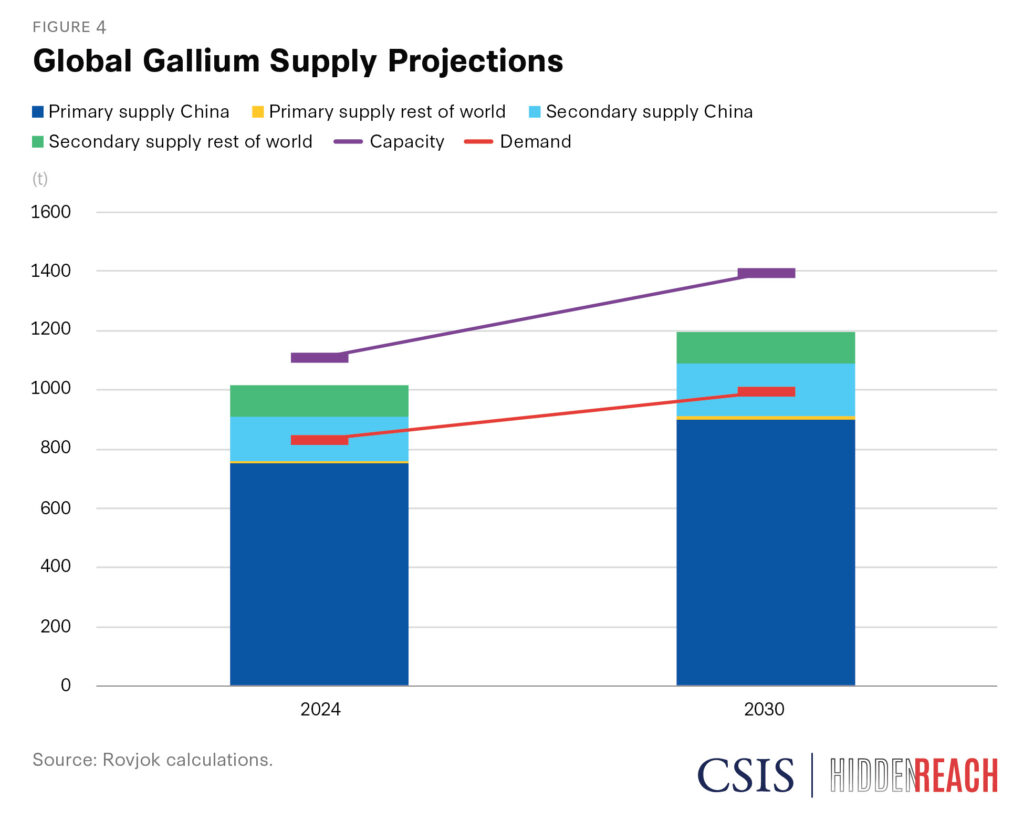

- Global dependence on Chinese primary gallium is now causing a gallium supply crunch that may soon impact key production lines as firms draw down their stockpiles.

- China’s most recent round of export controls on gallium extraction technologies could impede U.S. and allied efforts to quickly develop economically competitive alternative supply sources.

- Market forces alone are unlikely to solve the problem. Targeted government investment will be critical to breaking China’s gallium monopoly and undercutting its geopolitical leverage.

Responding to this mounting crisis will require the United States to take urgent steps to develop alternative sources of gallium supply and extraction technologies. Fortunately, the financial investments needed are relatively modest and promising solutions are well within reach—but only with a level of sustained policy attention that has only just begun to materialize.

Gallium’s Role in China’s Geoeconomic Strategy

China’s use of critical mineral export controls is not a new phenomenon, but it has evolved in recent years from a policy bludgeon to a precision tool. A defining early example came in 2011, when Beijing temporarily withheld rare earth exports to Japan amid a territorial dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. China backed off from those restrictions within months, but not before sending rare earth prices skyrocketing over 80 percent and leaving Japanese officials scrambling for alternatives.

In 2019, China trained this threat against the United States. As trade frictions flared under the first Trump administration, Chinese leader Xi Jinping publicly visited a rare earth processing facility in a conspicuous warning about the potential costs of further escalation.

Over the ensuing years, China further strengthened its hand by developing a legal and regulatory framework to transform these scattered actions into a comprehensive export control system. In 2020, the Chinese legislature passed the Export Control Law, which gave Beijing streamlined authorities to exercise “control on the export of dual-use items.” Unprecedented in Chinese export control regimes, the law included a provision claiming extraterritorial jurisdiction, meaning even entities outside of China could be held accountable for violating its statutes.

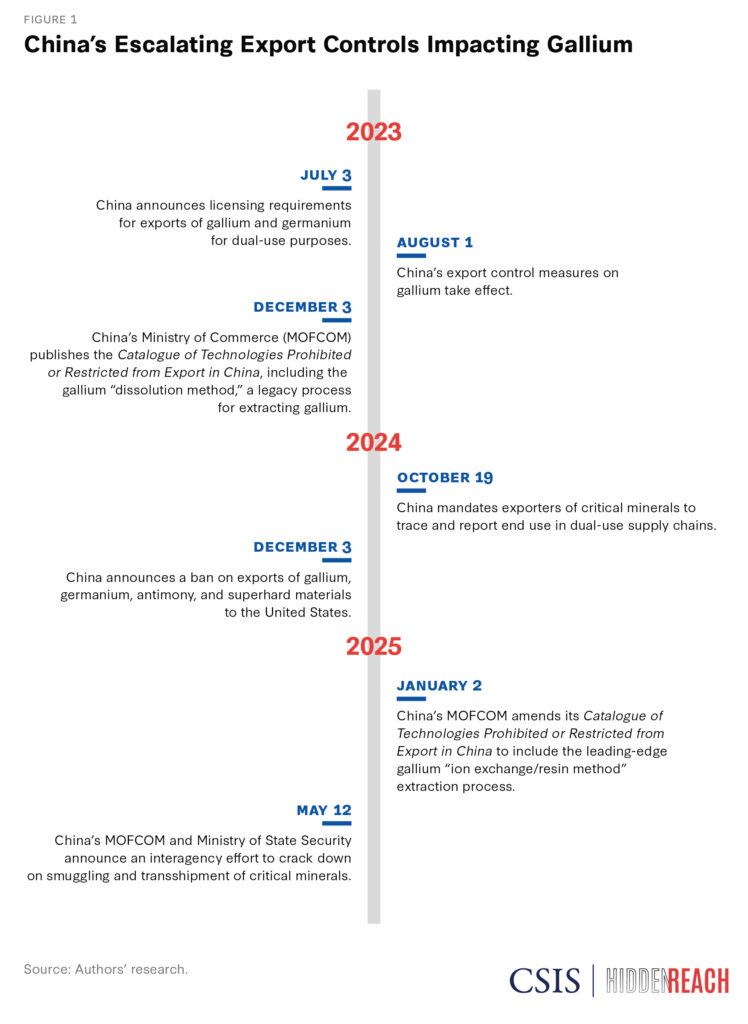

In July 2023, China put these tools to the test, announcing new licensing requirements limiting the export of gallium and germanium. The rules were broadly seen as retaliation against a series of landmark export controls put in place between October 2022 and July 2023 by the United States, Japan, and the Netherlands banning the sale of leading-edge chips and semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China.

China’s initial restrictions were cautious but calculated. Stopping short of an outright ban, they required gallium and germanium exporters to apply for licenses and disclose detailed end-use tracing information about their clients to China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM). Notably, MOFCOM emphasized that these measures did “not target any specific country.” Still, the move sent a powerful signal that if China’s semiconductor industry were denied Western chips and tools, China could deny the West crucial raw materials and intermediate inputs.

Beijing significantly tightened these restrictions as U.S. technology controls ramped up. In December 2024, the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security announced a package of expanded chip-related controls, including the addition of 140 Chinese semiconductor firms onto its Entity List. Just one day later, MOFCOM issued an update to its own export controls which functionally banned the export of gallium, germanium, antimony, and superhard materials to the United States.

The order marked the most stringent export controls China has put in place. For the first time, the ruling asserted the long-arm jurisdiction that China built into its Export Control Law years earlier, declaring that “any organization or individual of any country or region” would be held responsible for violating it. In effect, the rule formally outlawed the re-export or transshipment of gallium and other covered materials to the United States through third countries or territories, closing a major enforcement loophole.

Less than one month later, Beijing took its gallium export controls even further in a quiet but consequential move. On January 2, 2025, MOFCOM amended its export control catalogue to include several of the key extraction technologies used to separate gallium metal from its host ores (generally bauxite or zinc). The addition indicates that China is now taking steps to preserve its leverage over gallium supply chains by withholding the most cost-efficient means of extracting it.

In May 2025, China escalated once again by launching a coordinated interagency push to crack down on the smuggling and transshipment of restricted critical minerals. Coinciding with high-level U.S.-China trade discussions in Geneva, China’s State Export Control Work Coordination Mechanism Office convened over 10 central ministries—including MOFCOM and the Ministry of State Security (MSS)—as well as dozens of local officials to deepen enforcement over strategic mineral exports. China’s MSS has previously publicized its efforts to foil gallium smuggling attempts, but the new mechanism reflects Beijing’s deepened commitment to reinforcing its emerging export control system.

The creeping expansion of China’s gallium restrictions, from limited licensing requirements and end-user controls to full on embargos and long-arm export bans, offers important clues as to how the ongoing trade war may escalate. Beijing has already shown that it can use the progression of its gallium export controls as a playbook for choking off the United States and its partners from a broader range of strategic minerals.

Reassessing the Impacts of China’s Gallium Export Controls

Initial reactions in the United States to China’s gallium export restrictions downplayed the potential for disruption. In the months following China’s first 2023 announcement of its controls, company representatives, policy analysts, and government officials expressed confidence that production lines would remain unaffected and that alternative sources would quickly come online.

Leading chipmakers and downstream manufacturers reassured reporters and investors that their supplies were diversified, assessing that there would be “no material impact.” Citing international customs and trade data, analysts pointed to the low amount of gallium products imported directly from China to the United States to suggest that dependencies were negligible. Even U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan appeared unconcerned, remarking at a CSIS event in late 2024 that “there are other sources of . . . gallium in the world.”

Yet, these optimistic assessments obscured deeper structural vulnerabilities that have grown increasingly acute as China’s gallium controls have tightened. This analysis highlights three key developments which suggest that the risk of China’s gallium restrictions to U.S. and allied supply chains is greater than previously understood.

Key Point 1: Diverging prices within and outside of China reflect a growing supply crunch.

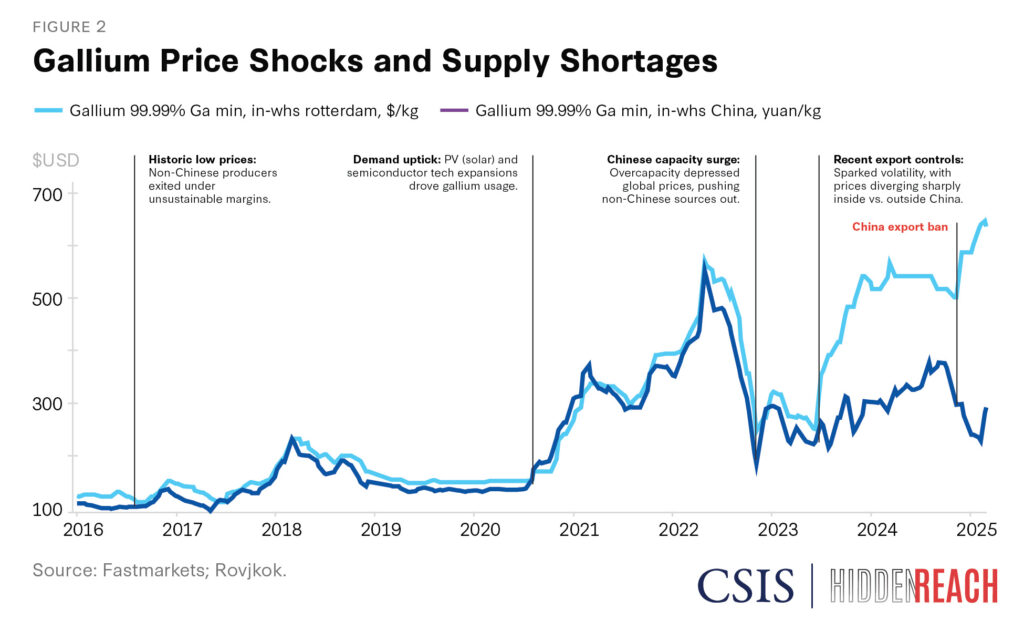

Since China’s export controls went into effect in August 2023, the price of gallium has diverged sharply between domestic Chinese and international markets. Within a month of the initial announcement, low-purity gallium prices in the Rotterdam exchange spiked by over 43 percent as Chinese suppliers halted shipments while applying for export licenses from MOFCOM.

This surge can be partially explained by a widespread rush by international buyers to stockpile gallium before the controls took effect. However, prices did not come back down even after demand stabilized, reflecting the impact of a supply-side squeeze caused by reduced Chinese exports of gallium.

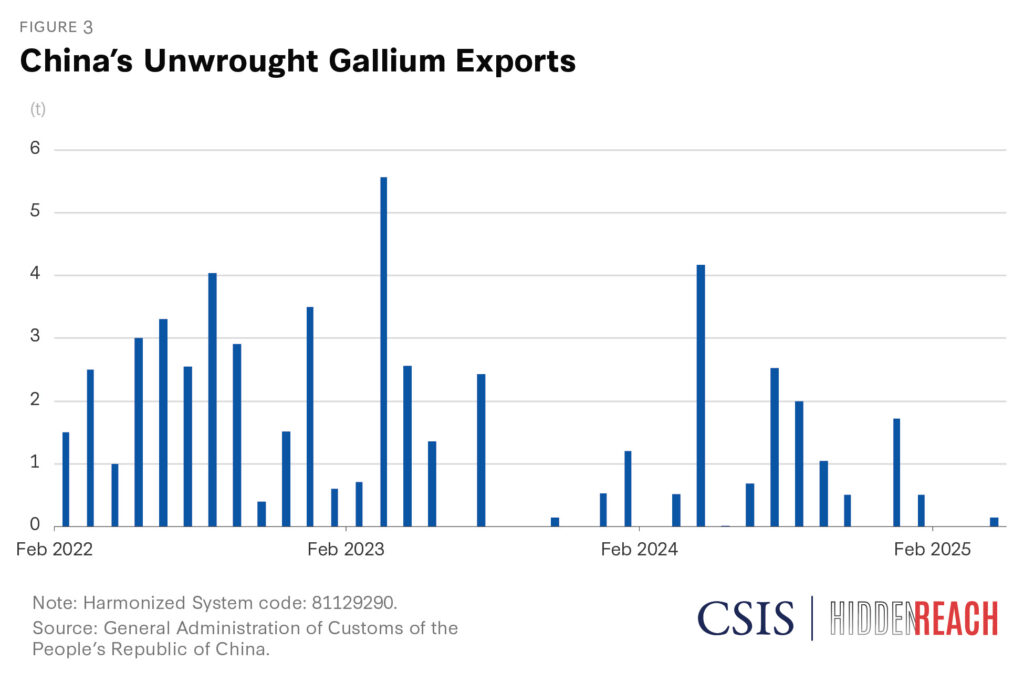

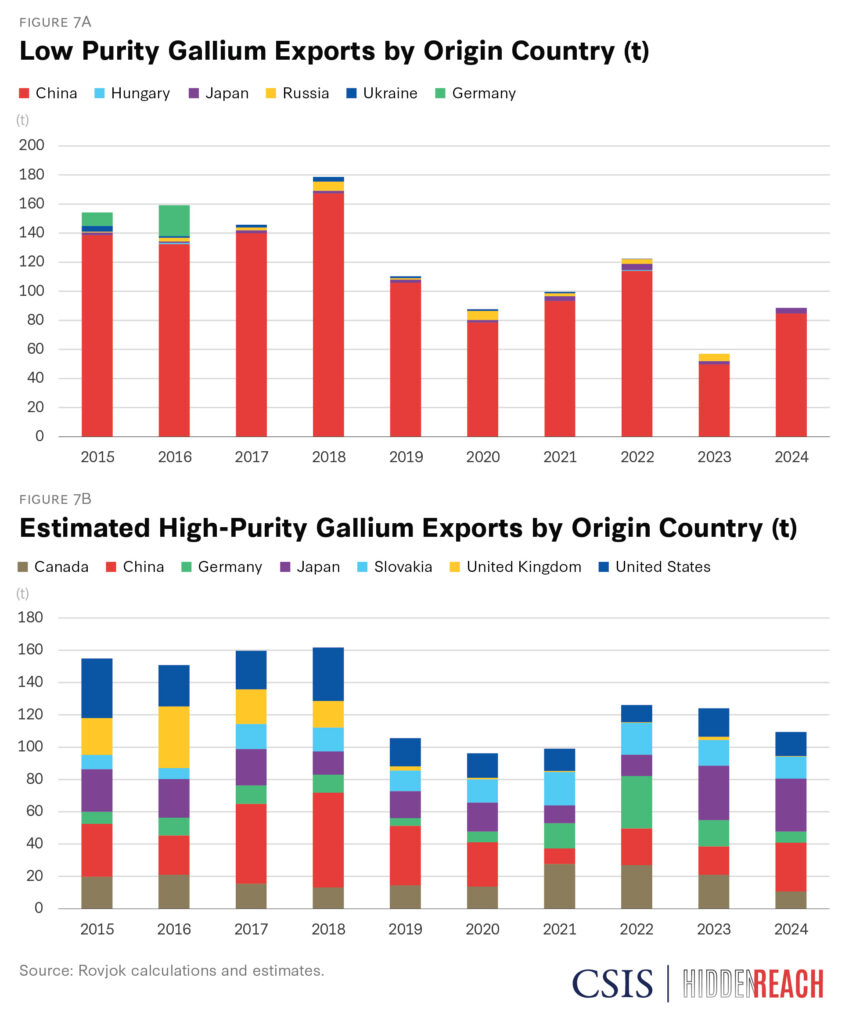

The cost of gallium outside of China, represented by its listed price on the Rotterdam exchange, has continued to significantly diverge from domestic price points as Chinese exports have fallen. By early 2024, prices appeared to have largely decoupled into two distinct markets, with gallium sold outside of China at nearly double the price of that within China (see Figure 2). Chinese customs data helps tell the story, showing that the country’s average monthly gallium exports drop significantly after August 2023 (see Figure 3).

These trends have intensified following China’s escalation of its controls to a full-scale embargo on the U.S. market beginning in December 2024. Tighter due diligence requirements, imposed by the extraterritoriality clause in the new controls, have further reduced China’s gallium exports and caused prices to surge to record highs. By mid-December, gallium prices jumped to their highest level since 2011 and continued to climb precipitously. In May 2025, the Rotterdam price of gallium reached $687 per kg, an increase of over 150 percent over pre-control prices.

Meanwhile, gallium prices within China have fallen due a combination of domestic oversupply and a lower demand outlook triggered by a recent shift in China’s photovoltaics industry away from technologies requiring gallium. The fact that this excess supply is not being exported, despite sky-high prices in overseas markets, reflects the seriousness of Beijing’s most recent controls.

Compelling anecdotal evidence provided by firms similarly points to a major supply crunch impacting not only U.S. companies but also major firms in allied countries like Japan and South Korea. Japanese officials and executives have expressed concern over the impacts of China’s newly escalated licensing requirements on gallium exports, equating the rules to “some sort of declaration of economic war against the rest of the world.” South Korean sources have similarly reported to the authors that Korean firms have been forced to wait months for licenses from MOFCOM, with some being denied.

These developments confirm analysts’ worst fears about China’s ability and willingness to meaningfully constrain global access to gallium. While the full extent of the impact of these measures on sensitive production lines remains unclear, companies downstream of the gallium supply chain could soon face dire challenges. The case of Henkel, a German producer of industrial adhesives that was recently forced to declare force majeure on its deliveries due to disruptions from China’s restrictions of antimony, stands as a dire warning.

Key Point 2: Non-Chinese sources of gallium remain reliant on feedstock originally sourced from China.

China’s decision to target gallium was driven by unique market dynamics that provide Beijing with an unusual degree of leverage over the mineral’s global supply. In 2024, China produced 98 percent of the world’s low-purity gallium, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS)—a figure well above its share of production of other targeted minerals such as germanium (68 percent) and antimony (48 percent). As a result of this near total monopoly, China can credibly withhold access to gallium supply from downstream markets, leaving buyers with few short-term alternatives.

The relatively small quantity of gallium consumed globally each year similarly provides China with acute leverage over markets. Annual demand for gallium is below 700 metric tons (t) internationally, a fraction of the massive markets for minerals like copper (25.9 million t) or nickel (3.1 million t). While demand for gallium is rising quickly, its comparatively small market means that even limited supply variations can have significant impacts on its global availability. This also makes gallium prices highly sensitive to minor supply adjustments, giving Beijing considerable leverage to manipulate market forces by artificially releasing or withholding flows.

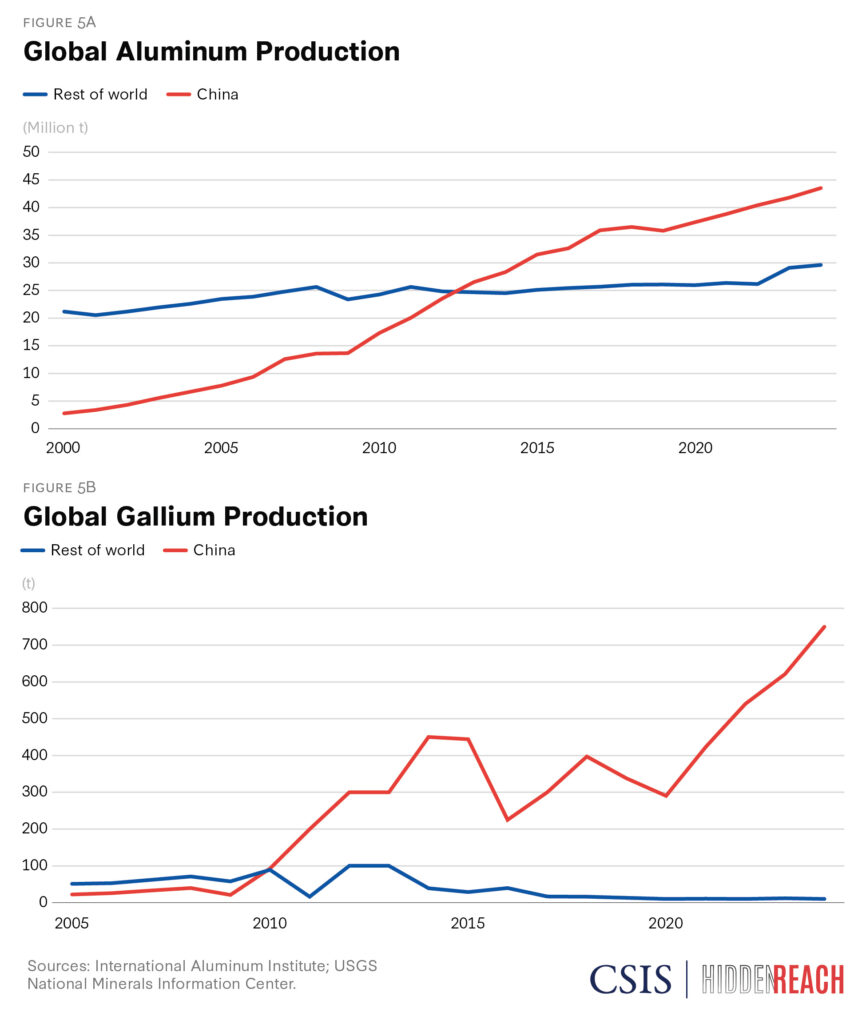

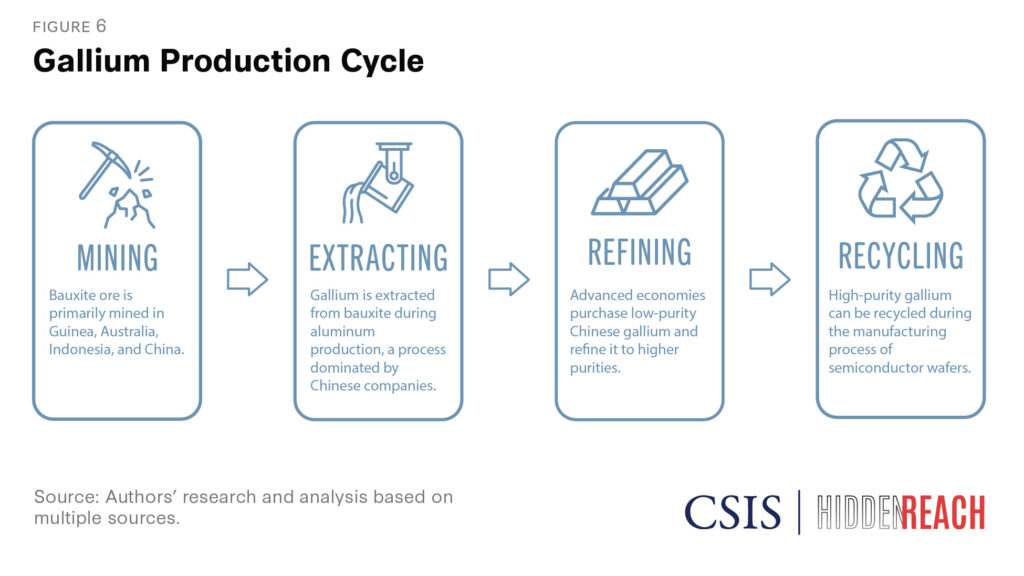

China’s stranglehold over gallium supply chains is rooted in its leading position in aluminum production. Gallium is not extracted directly from the earth—instead, it is recovered as a byproduct of processing other materials, primarily bauxite (the mother ore of aluminum), with a small amount also from zinc.

As China emerged as the world’s dominant producer of aluminum over the past two decades, it also developed the scale and technical capabilities to mass-produce gallium. Leading state-owned aluminum processors like the Aluminum Corporation of China (Chalco) were encouraged by state authorities to install the equipment needed to extract gallium from aluminum tailings. As China’s production of low-purity gallium began to explode and flood global markets around 2010, severe price fluctuations forced most of the leading non-Chinese suppliers out of the business over the following decade (see Figure 5a and 5b).

Left as virtually the only supplier in the world, China found itself with the means to translate its market dominance over gallium into geopolitical leverage in a way that few in the West saw coming.

Even firms not directly reliant on low-purity gallium could soon begin to feel the impacts of China’s restrictions. China’s direct dominance over gallium recedes further down the supply chain, diminishing to around 50 percent in the production of refined (high-purity) gallium and even less for intermediate products like gallium compounds and semiconductor wafers. Yet, these downstream inputs remain almost entirely dependent on gallium feedstock originating in China.

The relatively scant publicly available data on gallium flows has contributed to an illusion of supply chain resilience among some U.S. firms and analysts. The United States has never imported a majority of its low-purity gallium from China, creating the appearance of a diversified supply. Even after U.S. imports of Chinese gallium zeroed out following China’s 2023 export controls, the United States was still able to source imports from countries like Japan, Germany, and other partners, suggesting that it could easily route around Chinese controls. For high-purity gallium, the United States even has one domestically based supplier in operation, reducing its reliance on imports.

However, China’s new export controls should complicate this sense of security. MOFCOM’s licensing system now requires importers of Chinese gallium to provide detailed end-user tracing information, and foreign firms that supply U.S. companies with gallium at any point in the supply chain risk losing access to their only viable source of raw gallium if discovered. This creates strong incentives for foreign firms to halt service to their U.S. customers, as the marginal U.S. market for gallium likely does not justify the risks involved. These dynamics are further heightened by uncertainty over the extent of China’s enforcement.

China’s expanded controls could also begin to impact the few existing alternatives to Chinese gallium feedstock, which are primarily recycling facilities that recover gallium from scrap generated via the downstream wafer substrate manufacturing process. As an example, Japan uses approximately 40 percent of domestically recovered scrap and 60 percent primary low-purity gallium from China as feedstock into its domestic refining production. Still, the production capacity at its recycling facilities is limited and relatively costly, and ultimately it remains reliant on drawdowns from existing inventories that could gradually shrink as China further withholds upstream supply.

These challenges are reflected in a detailed 2024 study by the U.S. Geological Survey—published prior to China’s updated export controls—which estimates that a full-scale Chinese embargo of gallium could cause an $8 billion hit to U.S. gross domestic product. The largest projected losses were concentrated in the semiconductor industry, underscoring the vulnerability of strategic U.S. supply chains to China’s controls.

Key Point 3: New export controls on gallium extraction technology further undercut the price competitiveness for non-Chinese producers.

China’s dominant position over gallium supply chains extends beyond the raw material itself. A more opaque but similarly consequential constraint lies in the specialized resin technology used to extract gallium from bauxite ore processing.

As previously mentioned, China’s dominance over gallium production is not the result of a monopoly over access to deposits—gallium is fairly abundant—but rather its unmatched ability to extract the metal at scale and at lower cost. Chinese state-backed companies have outpaced global competitors by investing in the energy-intensive, chemically complex, and environmentally taxing process of extracting gallium from the Bayer liquor created during the processing of bauxite ore.

One of the most expensive steps in this process is isolating gallium from ore tailings at volumes that make production commercially viable. Chinese firms have innovated new methods of doing this at lowered costs. In particular, the chemical company Sunresin has developed a proprietary chelating resin tailored for gallium recovery. This resin outperforms older methods in both adsorption capacity and operational lifespan, allowing producers to extract more gallium per cycle with less material degradation.

As a result of China’s dominant domestic gallium industry, Chinese firms can produce these resins with economies of scale that their overseas competitors cannot match. Chinese facilities can thus produce gallium more cheaply and further extend their dominance, creating a positive feedback loop. This high-performance resin is critical to keeping China’s production costs well below what Western producers can match.

The challenge is compounded by the fact that this resin is neither widely manufactured outside of China nor readily substitutable. Sunresin produces as much as 90 percent of the global supply. While other methods of extracting gallium exist, they are more expensive and degrade more quickly, making it difficult for non-Chinese producers to compete with China on price, even under normal market conditions.

Recognizing the strategic value of this technology, Chinese authorities in 2025 quietly expanded their export controls to include the resin itself. A January update added “technologies for extracting gallium metal from alumina mother liquor using ion-exchange or resin methods” (通过离子交换法、树脂法等方法从氧化铝母液中提取金属镓的技术和工艺) to MOFCOM’s export control list. Industry sources have reported that exports of the high-performance resin have ceased entirely due to these new restrictions.

For the United States and its allies, this presents a fundamental obstacle to rebuilding domestic gallium supply chains. Even with feedstock and refining infrastructure in place, producers outside of China are unlikely to achieve competitive costs without equivalent resin performance. Until incentives are put in place to support the production of high-performance resin at adequate scale, non-Chinese producers will struggle to compete.

Gallium’s Strategic Significance

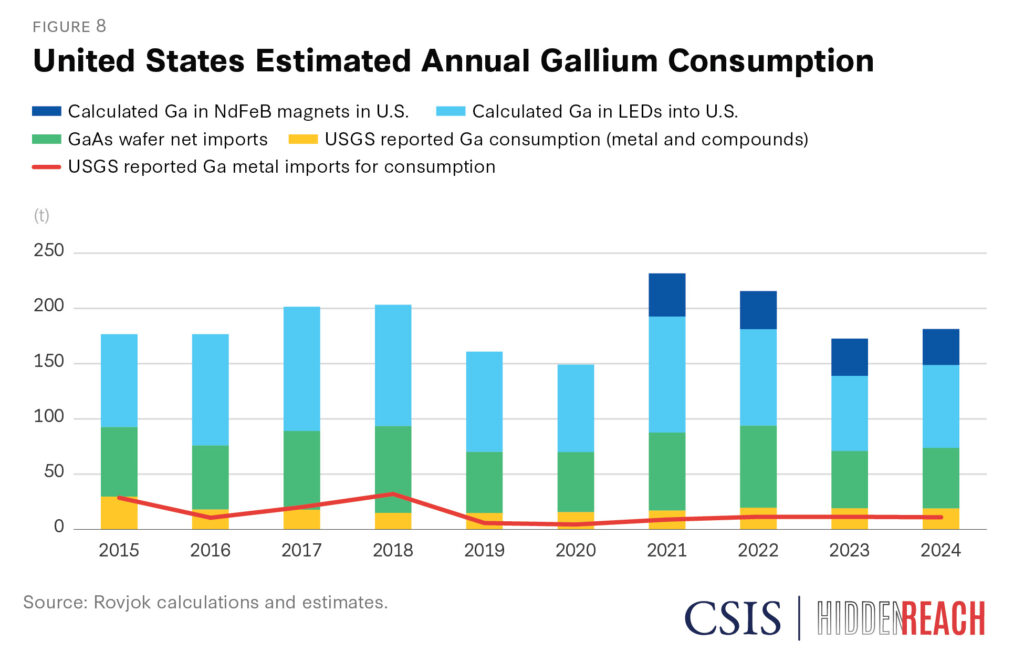

Gallium is used within a wide range of technologies, from advanced semiconductors to light emitting diodes, laser diodes, and permanent magnets. Yet, gallium’s true importance to the United States is not reflected properly in official reporting. The USGS shows gallium consumption in the United States to be around 20 t per year. However, taking into account imports of gallium-based wafers, magnets, and LEDs, consumption is likely far higher, up to 200 t per year (see Figure 8).

Critically, gallium’s outsized importance to key defense supply chains has elevated its value as a source of strategic leverage for China. China’s decision to open its controls with gallium—rather than other more commercially important minerals—allowed it to signal its capacity to disrupt U.S. and allied defense production while avoiding broader damage to its own economy.

The importance of gallium to advanced defense systems is difficult to overstate. Gallium compounds enable a class of “wide bandgap” semiconductors that outperform silicon in extreme operating conditions. Gallium nitride (GaN) transistors, for example, can operate at higher voltages and temperatures with lower losses, making them ideal for advanced radar, electronic warfare systems, and other applications requiring efficient power conversion.

U.S. defense systems have incorporated gallium-based technology for decades, but gallium compounds have taken on an increasingly critical role. Recent improvements in GaN chip design and falling fabrication costs have brought about rapid advances in next-generation radar technology. Widespread adoption of GaN chips has enabled smaller radar modules to track targets with higher resolution at farther distances. GaN-backed modules have been integrated into the U.S. military’s most important modern radar systems, including the Navy’s AN/SPY-6 radar, the Marine Corps’ G/ATOR radar, the Army’s LTAMDS radar, the Missile Defense Agency’s AN/TPY-2 radar, and the F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter’s upgraded AESA radar, to name just a few.

Gallium-enabled radar systems will also play an irreplaceable role in any efforts to build a layered nationwide missile defense shield, like the “Golden Dome” proposed by President Donald Trump. For example, Lockheed’s GaN-based Long Range Discrimination Radar—which is currently undergoing field testing in Alaska and will likely go into service next year—would form a crucial layer in the system’s defense against ballistic missile attacks.

Gallium-enabled radar systems will play an irreplaceable role in any efforts to build a layered nationwide missile defense shield, like the “Golden Dome.”

Meanwhile, the Department of Defense has invested millions of dollars in recent years to develop another emerging compound, called gallium oxide. Gallium oxide has an even wider bandgap and better performance potential than GaN, and it could form the backbone of a new generation of even more powerful and efficient defense electronic systems.

These and other technical developments have made U.S. and allied defense systems deeply reliant on technologies made with gallium. Open-source assessments reveal that over 11,000 individual parts used across the U.S. Department of Defense require gallium, and nearly 85 percent of defense supply chains containing gallium are known to include at least one Chinese supplier.

Key U.S. allies and security partners, ranging from Poland to Saudi Arabia to Taiwan, have also placed orders for U.S.-built GaN-enabled radar systems in recent years. As a result, supply vulnerabilities extend beyond the United States to its most important strategic partners.

Breaking China’s Monopoly

The extent to which China can derive leverage from its monopoly over gallium production fundamentally depends on how fast alternative supply sources can come online. If plants outside of China can rapidly begin or restart gallium extraction, then China’s ability to threaten global supply chains will quickly diminish. While promising initiatives are underway to establish new gallium production capabilities, decisive government action is needed to ensure these efforts are protected from China’s market manipulation.

The Limits of Market Forces

On its face, the gallium problem appears to have a clear market solution. As China restricts global supply, the rising global price of gallium should entice new producers into the market, creating alternatives to Chinese supply. The more China uses its leverage, the less it should have left.

However, the unique market characteristics of gallium discussed in the previous section mean that this challenge is unlikely to be solved by market forces alone. With near-complete control over the floodgates of global supply, Beijing can easily manipulate gallium prices to desired levels. In practice, this means that firms seeking to enter the market cannot guarantee that the market price of gallium will remain high enough to cover production costs. If alternative suppliers appear to be ramping up production, China could suddenly flood the market, cratering prices and erasing profits.

Gallium’s small market size relative to the huge aluminum market further adds to the challenge. For a Western alumina refinery, adding a gallium side-stream would impart additional complexity and risk for only a tiny fraction of the revenue generated by its alumina production.

China’s exclusive access to the most advanced resins used to extract gallium also gives its domestic refineries a significant cost advantage, further reducing incentives for foreign firms to compete. Absent market conditions that can support the scaled production of gallium extraction resins outside of China, non-Chinese firms will likely remain at a prohibitively large cost disadvantage in primary gallium production compared with their Chinese competitors.

These factors reflect the limits of relying on market forces to respond to China’s export controls. While current market conditions (characterized by rising demand, highly constrained supply, and high prices) have spurred considerable interest from new gallium producers worldwide, a long-term solution will require sustained government action if it is to incentivize firms to enter the market and stay there.

U.S. Domestic Opportunities

International Collaboration with Allied Producers

Rebuilding gallium supply chains at speed cannot be achieved through domestic sources alone. While establishing a reliable domestic supply is a reasonable strategic objective, it should be secondary to the urgent task of quickly developing large-scale gallium production outside of China. Ultimately, these efforts should prioritize projects that add gallium side-stream capacity at large-scale aluminum refiners, most of which are located outside of the United States.

Trusted partners in Canada, Australia, Japan, and Europe each bring unique capabilities and reserves that can narrow gaps in U.S. capacity. The recent designation of Australia and the United Kingdom as domestic sources for DPA funds was a critical step in leveraging allied advantages, but more international coordination with like-minded global partners is needed.

Canada already hosts North America’s only gallium producer, Neo Performance Materials. Although its operations are currently limited to recycling scrap inputs, it could help bridge the gap as primary production comes online. More significantly, Rio Tinto is exploring gallium recovery from alumina tailings at its Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean refinery in Quebec. If commercial-scale processing proceeds as planned, Rio Tinto could eventually supply 40 t of gallium annually—enough to meaningfully diversify North American supply.

Australia represents perhaps the greatest near-term opportunity for large-scale gallium production. Alumina refineries operated by South32 and Alcoa in Western Australia account for the largest such capacity outside of China, and given that gallium is recovered as a byproduct of alumina refining, these operations offer compelling economies of scale. Industry analysis suggests that building side-stream gallium recovery plants at these sites could be cost-effective and yield up to 40 t annually.

Separately, Nimy Resources is exploring secure gallium supply chains for U.S. defense applications through a collaboration with M2i Global. The partnership reflects the value of demand-side signaling from the U.S. government to spur up-front investment from private firms.

Japan, in partnership with the United States and South Korea, has committed to strengthening critical mineral supply chains, including gallium, under a trilateral framework announced in June 2024. Japan has a long history of utilizing gallium in its advanced electronics industry and is among the largest producers of gallium outside of China. The agreement highlights the shared priority of developing enhanced refining and processing capabilities—critical steps in reducing dependence on Chinese intermediates.

Europe also shows signs of renewed momentum. Greek metals group Metlen plans to extract gallium as part of a €295 million expansion to its alumina production capacity, aiming for 50 t of gallium annually by 2027. This initiative has been designated as a strategic project under the European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act, ensuring priority access to permits and financing. Meanwhile, Germany’s Stade refinery—once a major gallium producer—has announced plans to restart operations by 2027, potentially adding another 40 t per year to the global supply.

However, whether these new sources of supply will be accessible to U.S. buyers will depend on the evolving global trade landscape. The Trump administration’s tenuous relationship with many traditional trading partners may cause political roadblocks, and European policymakers may seek to channel the material to their own clean-tech and defense sectors first. Proactive U.S.–EU negotiations on long-term offtake agreements will therefore be essential to lock in access before production comes fully online.

Elsewhere, Kazakhstan—while not a traditional U.S. ally or security partner—previously produced primary gallium at the Padvolar refinery up until the early 2010s. It has recently suggested that production will recommence, with a target of 15 t per year from the second half of 2026.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

By doubling down on its gallium and other critical mineral restrictions, China’s leaders appear to have calculated that the country’s dominance over the global supply of minerals upstream of critical high-tech supply chains provides it with meaningful leverage over its rivals. Current trends reflect the worrying possibility that they could be right.

Ultimately, acting quickly to shore up these vulnerabilities is a critical test of U.S. and allied resilience against China’s emerging economic tool kit. Failing to respond effectively will send dangerous signals to Beijing about its ability to inflict asymmetric pain on the United States and allied economies. Fortunately, the United States and its global partners can take straightforward steps to neutralize China’s leverage.

If even a subset of the above international and domestic projects come online as planned, non-Chinese production capacity could grow by as much as 170 t—approximately 24 percent of current global supply. This would not only be sufficient to meet much of allied demand but could also help rebalance global pricing and undercut the effectiveness of China’s market manipulation.

To capitalize on these opportunities, policymakers should:

- Invest in a gallium defense stockpile using existing Defense Production Act authorities. The Department of Defense should expand its Strategic and Critical Materials Stockpiling Program to include at least 50 t of gallium over a five-year horizon. The stockpile should prioritize sourcing from non-Chinese suppliers under long-term offtake agreements and could be administered through the Defense Logistics Agency. Gallium has a shelf life of just one year, requiring careful inventory management to prevent degradation and ensure a reliable reserve during periods of supply disruption. The recently passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act provides $2 billion for critical minerals stockpiling through the National Defense Stockpile Transaction Fund. A small portion of these funds allocated toward gallium would go far in securing adequate supply for defense needs. Congress should also require an annual assessment of gallium supply adequacy under the National Defense Authorization Act to institutionalize visibility and planning.

- Expand federal matching funds for gallium and germanium recovery pilots at existing zinc and alumina refineries. The Department of Energy’s Office of Industrial Efficiency and the Department of Commerce should jointly create a pilot-scale retrofit fund—modeled on the 48C Advanced Energy Project Credit—specifically targeted at adding gallium recovery capabilities at existing facilities like South32’s Worsley Alumina in Western Australia and Nyrstar’s Clarksville Smelter. Matching should prioritize first-mover projects in facilities that coproduce high-purity alumina or zinc, where side-stream economics are most viable. These agreements should also be supported with floor-price and guaranteed offtake arrangements backed by stockpiling mechanisms.

- Create a joint procurement mechanism with allies to de-risk early production volumes and stabilize demand signals. The United States should work with Japan, the European Union, and Canada to establish a pooled purchasing program—similar to NATO’s Strategic Airlift Capability—to jointly contract initial volumes of gallium from new projects. This could take the form of forward offtake agreements with price floors indexed to Chinese domestic gallium benchmarks, insulating new producers from deliberate undercutting by Beijing. Procurement agencies such as the U.S. Defense Logistics Agency, Japan’s JOGMEC, and the European Union’s EIT Raw Materials could coadminister this initiative.

- Strengthen multilateral coordination through the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) to ensure cross-border investment, data sharing, and streamlined permitting for critical mineral projects. MSP members should create a shared project tracking database for gallium-relevant extraction, refining, purification, and recycling initiatives, including harmonized data on projected output, permitting status, and investor needs. Additionally, the United States should propose the creation of a “fast track” gallium permitting lane for projects in allied jurisdictions, modeled on the Five Eyes’ clean energy infrastructure cooperation frameworks. The MSP could also coordinate diplomatic engagement with European nations where gallium projects are underway, such as Greece and Germany, to ensure U.S. access to gallium produced under EU strategic materials programs.

Aidan Powers-Riggs is an associate fellow for China analysis with the iDeas Lab at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Brian Hart is deputy director and fellow with the China Power Project at CSIS. Matthew Funaiole is vice president of the iDeas Lab, Andreas C. Dracopoulos Chair in Innovation, and senior fellow of the China Power Project at CSIS. Scott Thomsett is CEO of Rovjok, a critical minerals intelligence firm in Helsinki, Finland. Simon Zieleniewski is a director at Rovjok. Tim Rose is a director at Rovjok.